- Tyson is closing its Lexington beef plant in January, cutting about 3,200 jobs and devastating a town that depended on the plant for decades.

- The closures (plus Amarillo cuts) reduce U.S. beef capacity 7–9%, hurting ranchers, supply chains, and potentially keeping consumer prices high.

OMAHA, Neb. — In the flat, wind-swept plains of central Nebraska, where the Platte River snakes through fields of corn and cattle, the news hit like a sudden storm.

Tyson Foods, the giant of American meatpacking, announced last week it’s shuttering its massive beef processing plant in Lexington—a facility that’s been the lifeblood of this small city for decades.

The closure, set for January, isn’t just a corporate footnote; it’s a seismic shift that could upend an entire community and send shockwaves through the nation’s ranching heartland.

The FrankNez Media Daily Briefing newsletter provides all the news you need to start your day. Sign up here.

Lexington, with its population hovering around 11,000, has long danced to the rhythm of that plant.

Opened in 1990 and later snapped up by Tyson, the facility employs about 3,200 people—nearly a third of the town’s residents.

On a good day, it churns through 5,000 head of cattle, turning live animals into the steaks, burgers, and roasts that fill grocery coolers coast to coast.

Now, with those gates set to close, the air feels heavier, laced with uncertainty.

Families who built lives around steady paychecks are staring down an abrupt void, and the town’s economy, so tightly woven around Tyson’s operations, is fraying at the edges.

Official Announcements

Clay Patton, vice president of the Lexington-area Chamber of Commerce, didn’t mince words when he described the announcement that came down on Friday.

“It felt like a gut punch to the community in the Platte River Valley that serves as a key link in the agricultural production chain,” he said Monday.

Patton’s been watching this town transform over the years, from a fading dot on the map to a bustling hub that drew immigrants from across the globe to its factory floors.

The plant nearly doubled Lexington’s population, sparking a wave of new businesses, homes, and hope.

First-generation entrepreneurs opened shops catering to workers from Mexico, Sudan, and beyond; housing developments sprouted up to accommodate the influx.

But come January, those gains could unravel. “The ripple effects will be felt throughout the community, undermining many first-generation business owners and the investment in new housing,” Patton warned.

Tyson is dangling a lifeline—offering displaced workers relocation packages to other plants, some hundreds of miles away.

The Impact of the Closure on the Working Class

It’s a tough sell for folks with roots sunk deep into Nebraska soil, families tied to schools and churches they’ve called home for years.

“I’m hopeful that we can come through this and we’ll actually become better on the other side of it,” Patton added, his voice carrying that Midwestern grit, the kind that refuses to fold without a fight.

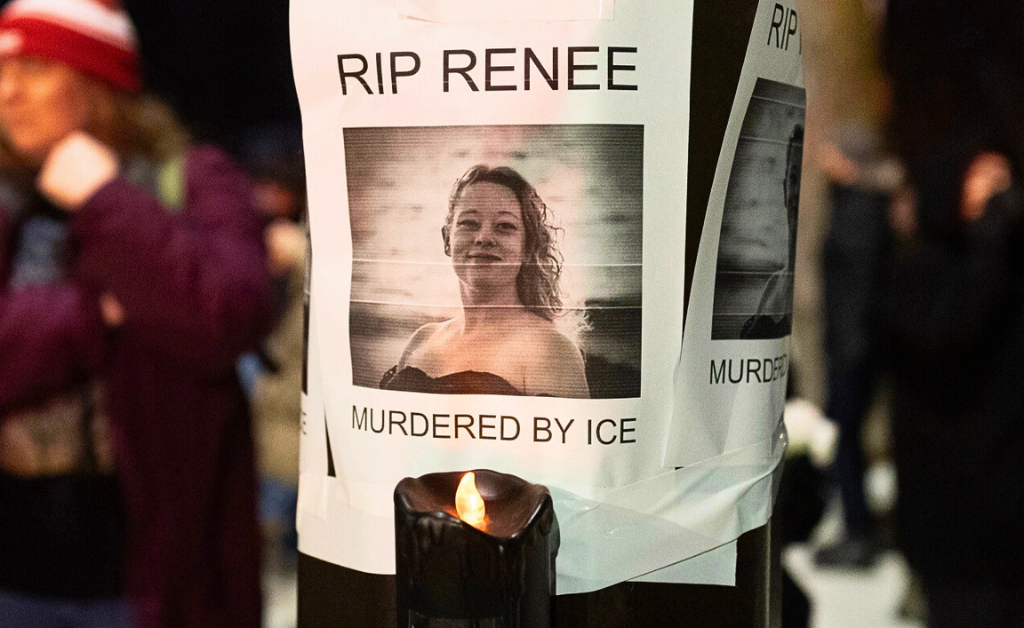

The human toll is already palpable.

Elmer Armijo, who arrived last summer to pastor the First United Methodist Church, was still settling in when the news broke.

He’d been drawn to Lexington by its stability: solid jobs, strong schools, reliable health care, and a sense of forward momentum.

“When I moved to Lexington last summer to lead First United Methodist Church… (the community had) solid job security, good schools and health care systems and urban development—all in doubt now,” he reflected.

Now, his congregants are anxious, whispering about mortgages and moves.

“People are completely worried. The economy in Lexington is based in Tyson.”

Churches like Armijo’s are stepping up fast, rolling out counseling sessions, food pantries stocked with non-perishables, and even gas vouchers to help families stretch their dollars.

It’s a patchwork response to a wound that’s just starting to show its scars, but in a town this size, everyone knows someone affected.

The local schools, which once swelled with the children of plant workers, might see enrollment dips; the diners and dollar stores could empty out by midday.

Zoom out from Lexington, and the stakes climb even higher.

Nebraska Plant Isn’t the Only One

This isn’t an isolated cut—Tyson is also trimming one of two shifts at its Amarillo, Texas, plant, axing 1,700 jobs there.

Combined, these moves will slice U.S. beef processing capacity by 7% to 9%, a chunk big enough to rattle the supply chain.

Ranchers across the Midwest and Plains, who ship their herds to places like Lexington, are watching cattle prices tumble in the fallout.

Fewer slaughterhouses mean fewer buyers, and with that, the hard math of feed costs and slim margins gets uglier.

Bill Bullard, president of the Ranchers-Cattlemen Action Legal Fund United Stockgrowers of America, captures the mood in the pastures.

“There’s just a lack of confidence in the industry right now.

And producers are unwilling to make the investment to rebuild,” he said.

It’s a vicious cycle: High beef prices at the store—already at record levels, fueled by droughts that scorched grazing lands and tariffs that jacked up import costs—aren’t trickling back to the ranchers who raise the animals.

Instead, they’re squeezed, hesitant to expand herds when the payoff feels so distant.

Enter the wildcard from Washington. President Donald Trump’s recent slash of tariffs on Brazilian imports could flood the market with more South American beef, potentially easing sticker shock for consumers.

Brazil already supplies 24% of U.S. beef imports, mostly lean trimmings that bulk up ground beef rather than premium cuts like ribeye.

Trump touted this move last week as a win for American shoppers, but for ranchers, it’s salt in the wound—more competition when they’re already reeling.

As Bullard puts it, the timing couldn’t be worse, amplifying doubts about the viability of U.S. cattle operations for years to come.

Experts Weigh In

Glynn Tonsor, an agricultural economist at Kansas State University, tempers the panic just a bit.

Predicting next year’s import levels—hovering around 20% of the U.S. beef supply—is tricky, he notes, especially with tariffs flipping like Midwest weather.

“It’s hard to predict whether imports will continue to account for roughly 20% of the U.S. beef supply next year,” Tonsor said.

“He pointed out that Trump’s tariffs have changed several times since they were announced in the spring and could quickly change again.”

Still, one thing’s steady: Americans’ love affair with beef.

We’ll devour about 59 pounds per person this year, even as prices climb, blending imported trims into everyday patties without batting an eye.

At the corporate level, Tyson’s move makes cold, calculated sense.

The beef division has been bleeding red—$720 million in losses over the past two years, with another $600 million expected this year.

The industry groans under excess capacity; there are more slaughterhouses than needed, a push from regulators to foster smaller players and break the grip of behemoths like Tyson.

But in Lexington, that efficiency play feels abstract.

Ernie Goss, an economist at Creighton University in Omaha, chalks it up to tech’s relentless march.

“It’s very difficult to renovate or make the old plant fit the new world,” he explained, drawing from a recent study on a cutting-edge beef facility.

The Lexington site, he said, “just wasn’t competitive right now in today’s environment in terms of output per worker.”

Tonsor agrees it’s no surprise. “It was inevitable that at least one beef plant would close,” he observed.

“Afterward, Tyson’s remaining plants will be able to operate more efficiently at closer to full capacity.”

Related: Verizon Now Announces Massive Layoffs Over 15,000

What Happens Now?

For the company, it’s a path to profitability; for the workers packing up tools and the ranchers scanning markets, it’s a grind toward an unclear horizon.

As January looms, Lexington braces.

Patton and others are rallying—scouting new industries, pitching the town’s resilient spirit to investors.

Armijo’s sermons now lean toward endurance, drawing from stories of communities that bent but didn’t break.

Nationwide, ranchers huddle over futures contracts, weighing whether to hold steady or scale back.

And in supermarkets from Omaha to Orlando, the price tags on sirloin might hold pat for now, thanks to the backlog of cattle in the pipeline.

But longer term? Unless incentives flip and herds grow, those record highs could etch even deeper.

It’s a reminder of how fragile the chain is—from Nebraska feedlots to your backyard grill.

One plant’s end isn’t just local lore; it’s a thread pulled loose in the fabric of how America eats.

Also Read: A Popular Bank is Now Quietly Closing 51 Branches